Words and images by Sports Garage Ambassador Brian Firle.

Photo: Colorado Trail Foundation

Four months ago when a close friend asked me if I wanted to ride the whole Colorado Trail in September, I was apprehensive.

I hadn’t really caught the ‘bike-packing’ bug and the idea of tackling some of Colorado’s most rugged and remote trails with 30 pounds of extra gear on my bike didn’t really strike me as fun. But once he pitched me his vision for the trip, I was in.

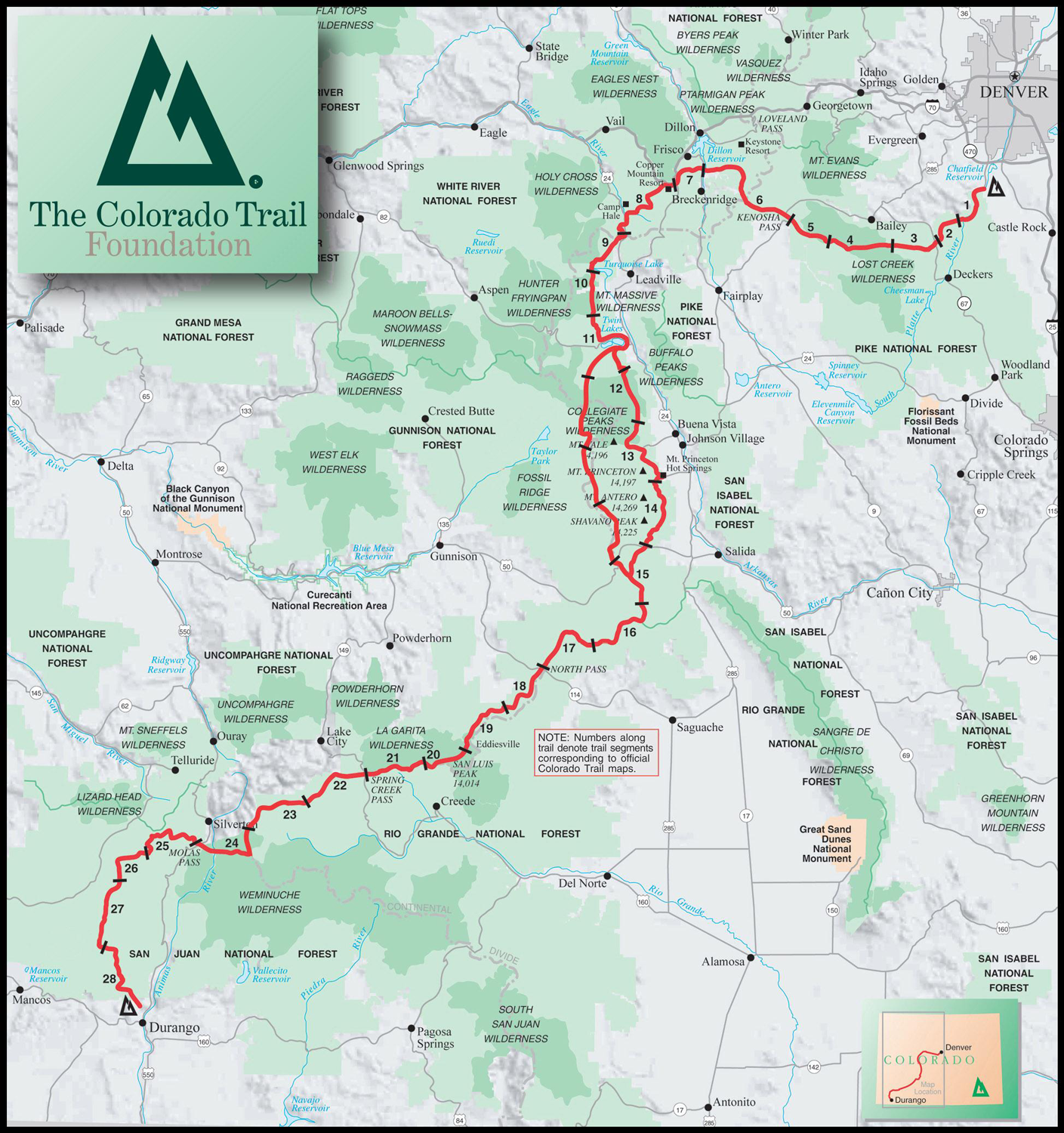

There are many ways people have attempted to travel the Colorado Trail in its entirety. Most people hike it, backpack and all, and generally take 4-6 weeks to conquer the whole 485 miles. But when you want to travel by bike, the trail crosses six wilderness areas that do not allow motor vehicles or bicycles to travel through them. So, because you must do six detours around those wilderness areas on gravel roads and highways, you add 80-ish miles to the journey totaling something like 550+ miles, with 80k feet of elevation gain.

Long story short: it’s a hell of a bike ride. Most people who ride the whole trail bike-pack it in anywhere from 2-3 weeks. Our goal was different.

What if you could ride the whole Colorado Trail stage-race style?

Meaning, what if you could section the trail into huge days where you only carried what you needed for the day, and then had someone move your gear from night to night? An extremely generous friend volunteered for the position of soigneur/cook/van-driver/camp-host and we sectioned the trail into nine days of riding.

Nine days to cover 550+ miles of high alpine single-track from Denver to Durango, averaging 65 miles a day and 8,000 feet of elevation gain. Seems doable right? Even when I looked at the numbers for the trip, the trail, the whole thing, I thought, “Couldn’t we do this faster?” Is this really going to be that much of a challenge? What if we did it in seven days and made a few days shorter? After all, we wouldn’t be carrying all our stuff.”

After years of racing bikes at an elite level, both on the road and the mountain bike, I thought, “How hard could this be? We’re not racing the thing. You just get on your bike and ride.” I wasn’t really intimated by the idea of riding the whole CT.

I knew it would be hard, but not as hard as it was. By day five when we were crawling through snow and hundreds of down trees on Monarch Pass, I cracked. Not so much physically, but mentally. And that was a surprise to me. If anything, I thought my breakdown would be physical: my back, knee problem, crashing, or the like. But as turned out, it was the mental strength that I felt I lacked.

High alpine days left the crew short of breath, but the views were phenomenal.

A typical day looked like this:

Wake up at 6:30am feeling tired and hungover from the previous day of riding – lack of sleep, lack of food, lack of electrolytes. You crawl out of your sleeping bag like a creaky tin-man, put on two puffy jackets (it was cold), get some coffee, and attempt to put food in your mouth and stomach.

Prep your bike, prep your body, get your stuff organized. Try to eat again, try to drink more water. Doing everything you can to replenish the 8,000 calories you burned the day before. Try to eat again. Poop. Get all the food you might need for the day plus a few liters of water and roll out around 8:30am.

Ride some of the most rugged, remote, and challenging single track between 10,000 and 13,000 feet. All. Damn. Day. Imagine taking your longest trail ride you’ve ever done in the high country…4-5 hours maybe? Then double it.

Exhausted, you might get to the campsite by 5pm or 6pm or 7pm, once time 8pm. Fall off your bike onto the ground from exhaustion. Scrounge around for your gear. Set up tent. Wash your butt out with some hot water from a jet-boil. Change clothes, put both puffy jackets back on. Attempt to eat food (which doesn’t go well). You’re starving but you are still at 10,000 feet and you have been eating pop-tarts all day long so your stomach feels terrible. Try to drink more water and electrolytes. Eat more food than you feel like. Poop again. Wipe down bike and prep stuff for the morning. Lube chain, get more food and fill camelback because you won’t want to do it in the morning when its 27 degrees. Go to bed, attempt to sleep at high altitude. Sometimes you sleep hard. Sometimes you don’t.

Wake up at 6:30am, do it all over again. Day after day. Sounds fun right? It was.

Balancing challenges on and off the bike, the CT never ceased to confront us with a new adventure each and every day.

This is what we call a mixture of “type one” and “type two” fun.

Type one is the easy, low-hanging-fruit fun: movie night, hanging in the backyard with friends, water skiing. But type two fun is reserved for us masochists: mountaineering, bike racing, multi-pitch rock climbing, ultra marathons, and idiots that ride the whole CT in nine days.

This was the blend we were going for: something hard enough that pushed us mentally and physically, but not miserable enough to make it all feel like work. It could be argued either way but I think we found a good balance. 🙂

Either way, I cracked mentally on day five and it took all of one or two days for me to get over the hump. I even yelled at my best bud on the trip with me, telling him that his positive attitude was “dumb as hell.” By day seven, the “queen stage” day through the San Juan Mountains, I was feeling awesome. Tired, albeit, but mentally engaged, filled with gratitude, and enjoying the trail experience to the fullest. I had slowed down a bit internally, not feeling the pressure of getting through the trail as fast as we could to make it to camp before dark. Day seven (from Spring Creek trailhead, outside of Lake City to Silverton), was an epic day. 56 miles and 10k feet of climbing—with a total of 40 miles of continuous single-track above 12,000 feet through some of the highest and most rugged parts of Colorado’s mountains. This was a day that just kept on giving—grinding up the scree fields along the ridge-line and plummeting down the saddles between the peaks. The second you’d touch the high point of the next ridge, down you’d go to the saddle below, only to climb back up to the top of another ridge, or skirt around another peak. There aren’t words to really put to how incredible (and difficult) this day was. The temperature was perfect, cool but not cold, the sun was out, making paintings in the smokey sky and lighting up the colors of every plant on the mountainside.

Cracked and deep in the hurt locker: type 3 fun.

At the final climb of the day, I found myself in the company of two other friends from our trip. At 5:30pm, golden hour, we were standing on the edge of a 12,000 foot ridge, looking down into a valley of yellow and green ferns, maroonish grass, and bright red flowers. It was dead silent. There wasn’t another person probably 50 miles from us. I can close my eyes and still see the sun casting shadows in the warm valley. The little stream that twisted its way through the alpine grasses. And a complete 360 degree view of high peaks in all directions. The whole day felt like we were riding through the sky.

I wonder if this was the reason that God was always calling people to the mountaintop?

Because it is there and only there can you see the world through his eyes. Just for a moment we get to witness the big-ness of our world and our tiny place in it.

There is only one response that seemed natural at that moment like that: gratitude. Gratitude that I have a body that allows me to take adventures like this. Gratitude that I have loving people around me that empower me to push myself. Gratitude that with all the hurt and pain in the world, we get to escape it for just a few days—to retreat to a wild place and think about nothing other than “should I take the A-line or the B-line?”—the simplest of things.

All in all the trip was incredible.

There are so many stories, both on the bike and off that I could share. It’s crazy to me how novel warm water is after nine days of not having it, how dry your skin can get when you don’t put on lotion every day after a shower, and how amazing fresh lettuce is when all you’ve eaten is pasta and dried meat. How lucky are we that we get to willingly deprive ourselves of such things, only to easily return to them when the trip is over.

Sitting in the living room of my home in Boulder, CO, back to the grind and sometimes mundaneness of everyday life, I take myself back there. I close my eyes and I can feel my beating heart pounding out of my chest as I pushed my bike over Searle Pass. I can see all the valley above the township of Cathedral, where the sun was setting over the mountains and casting beams down to the small farms below. I can feel the dry wind and sand on my face as we detoured on 60 miles of gravel road after Sergeants Mesa. I can feel the burn in my shoulders and hands after descending for 10 miles off high mountain ridge.

All these experiences are what fuel and power my love for the sport.

In the moment we can pass right though them, remain unaware of the beauty that is set before us and within us, distracted by the beehive in our minds. The reason I go on these adventures is because they center me, challenge me, and expose me to a beauty that I would never have witnessed otherwise: the emotional breakdowns, the body aches, the trail ripping speed, the hi-fives, the “uffdah’s” after a big climb, the crashes, and the “sendable” sections. It’s not just the perfect moments, but it’s the whole journey that entices me out into the woods. I can always know that when I am detached from boujie facets of modern life, that I will experience a beauty otherwise unknown.

My hope is that we all do this in our own way. Mine tends to look like this Colorado Trail trip, but thats just my prescription. What might yours be?